Flower dissection is a lovely, simple practical to do. Some flowers are large enough to clearly see the different parts and are easy to manipulate, some also contain both male and female parts (lily, hibiscus, tulip).

It is important for students to appreciate that it is not only animals that undergo sexual reproduction but that plants also have this ability and have male and female organs containing the reproductive cells.

Reproduction in Plants

Female parts of a flower: stigma, style and ovary (collectively: the carpel, or pistil). The ovary contains ovules (female gametes).

Male parts of a flower: anther, filament (collectively: the stamen). Pollen sacs inside the anther contain pollen cells which contain pollen grains (male gametes).

For fertilisation to occur, the plant needs to move pollen from the anther of one flower to the ovule of another (pollination).

Moving pollen from a flower is most often done by insects, specifically (but not exclusively) bees.

Flowers attract bees to them by being highly coloured/aromatic and containing nectar, a sweet treat that bees and other insects cannot resist.

Wind pollination is also a popular method of transferring pollen away from the plant. These plants tend to have less showy flowers (e.g. hazel catkins) and the stamens hang down to allow the wind to move them (and release the pollen)

Once the flower has attracted the insect in to retrieve the nectar, the pollen, ready to be removed by sitting on the top of the anther (or all over it) gets stuck to the hairs on the body of the insect.

When the insect flies off to visit another flower it loses the pollen as it delves deep into the flower to collect nectar, the pollen grains get stuck onto the sticky stigma and are taken down to the ovary where they fuse with the female ovules (1 pollen grain per ovule), and fertilisation takes place.

Self-fertilisation can occur if pollen from a flower is dropped back onto the stigma of the same flower. This is not an ideal situation as it limits genetic mixing between different flowers and can increase the risk of a genetic defect being passed on down the generations and ultimately killing the species. Many plants have adapted ways of preventing self-fertilisation (self-pollination) by having female and male parts on different parts of the plant, or by these parts maturing at different times, or by being ‘self-fertile’ which means the pollen is not able to fertilise the ovule of the same flower.

The bright petal colour and presence of nectar help to avoid self-pollination by attracting insects to remove the pollen from the flower (and bringing in different pollen).

Dissection of Flowers

SAPS recommend Alstroemeria, a flower regularly available in supermarkets, for dissection.

- Sepals

The process of flower dissection should start with a mention of the protective covering that the sepals (‘first’ outermost leaves – sometimes looking like extra petals) provide for the emerging flower, which contains the male and female parts.

- Male parts of the flower: (anther, filament, pollen)

Remove the stamen (anther and filament) from the flower and, if the flower was open before you started the dissection, you will see pollen covering the outside of the anther. This pollen is ready to transfer to another flower (in horticulture people will remove some of this with a fine brush and fertilise a second (chosen) flower using the pollen from the brush, if they are looking to grow a specific flower colour for example).

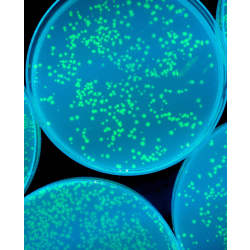

You can look at the pollen grains under a microscope.

Pollen is highly individual and specific to the plant, so if you have some different plant flowers to dissect you could look at the different pollen grains and discuss the shapes and styles and how this may help pollen dispersal (e.g.: hooks allow pollen to stick to hairs of insects, air sacs and smooth edge indicate a wind-pollinated plant).

If the flower was still in bud when you do the dissection, you may be able to see dividing cells if you squash and stain the grains, although this is a tricky process (A level).

- Female parts of the flower: (stigma, style and ovary)

The ovary can be found in the base of the flower, the swollen top of the stem. Cut into this and you will find the ova. The top of the style is the stigma. This is sticky so that the pollen can stick to it, it is not the nectar. The nectar, found in the very base of the flower, encourages insects to come right to the bottom of the flower, brushing past the stigma transferring pollen, and thus enabling fertilisation.

Fertilisation, the pollen meeting and joining with the ovum, results in the formation of seeds within the ovary, which then develops into the fruit.

The main function of the fruit is to protect the seed as it develops and to aid the seeds’ dispersal (either by being taken and eaten by animals, by drying and being dispersed by wind, or by drying, opening and sometimes exploding to allow a good, wide spread of the seed), which can then begin germination into the plant, once the external conditions are appropriate.